At this time last year, Lydia Peelle was selected to receive one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 fiction awards for her short story collection, Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing. I’d read her collection some months prior to the announcement and was excited to hear of her nomination. While reading the collection, I’d been captivated by the way Peelle told a story. The characters she wrote of felt vibrant, though their lives often were not; the settings were so raw and crisp it was offensive; the dialogue was quiet yet piercing. Peelle was a no-brainer for the award.

At this time last year, Lydia Peelle was selected to receive one of the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 fiction awards for her short story collection, Reasons for and Advantages of Breathing. I’d read her collection some months prior to the announcement and was excited to hear of her nomination. While reading the collection, I’d been captivated by the way Peelle told a story. The characters she wrote of felt vibrant, though their lives often were not; the settings were so raw and crisp it was offensive; the dialogue was quiet yet piercing. Peelle was a no-brainer for the award.

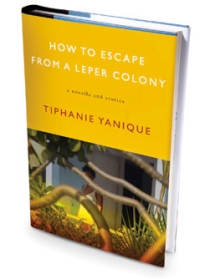

This year, Tiphanie Yanique has been selected to receive the award for her debut collection, How to Escape from a Leper Colony. I wanted to finish reading the collection before coming on here and telling you like it is. But then again, I’m not the best at keeping things to myself, and I hate to withhold evidence, especially when it’s this good. Though I’ve only read the opening story, How to Escape from a Leper Colony, from which the book gets its name, you always know when you’re getting yourself into something worth talking about. In reviewing the book (a collection of a novella and seven stories), Cristina Henriquez said, “I loved every minute of this book and was in awe of nearly every paragraph.” Some hefty praises, Henriquez. But also, if the opening story is any indication, spot on.

In the first passages of How to Escape from a Leper Colony, Yanique dumps readers on an island in the Caribbean, much like how the narrator of the story, Deepa, with her leprous arm, has suddenly been abandoned by her mother to be taken in by nuns and volunteers at the leper colony. The reader gets accustomed to life on the island in time with Deepa — we’re with her when she’s assigned a roommate, when she has her first surgery, and when she learns that nuns receive special burials on the island. We’re there, too, when she meets Lazaro, an outsider living on an island for outsiders: Lazaro isn’t leprous nor a volunteer, his ethnicity (Indian or African?) is unclear, and he desires to partake in religious rituals of which he’s been excluded. It’s these qualities, plus a difficult history  involving the murder of his mother, that leads Lazaro to take bold action in rendering all the island’s citizens equal.

involving the murder of his mother, that leads Lazaro to take bold action in rendering all the island’s citizens equal.

Yanique’s poetic language enraptured me. Even when her characters were speaking in their craggy English — “Is your father they burning tomorrow?”, “We here because God want somebody to know him” — the language still came out natural and authentic, pleasing in its own way, and the reading was fluid. The imagery of the island, the energy of Deepa and Lazaro, the sadness of the circumstances — they all fell gracefully in line with Yanique’s language, and made an elegant story out of painful seclusion.

Whatever Yanique has in store for me with the rest of her collection, I’m in. She brings a new sensibility and a fresh voice to the craft of short fiction. I’m a sucker for all of it.

—S